For the Ways, the two sides seem to be, largely, the Rajneeshees and the U.S. The directors’ decision to limit the number of Rajneeshee subjects is an effective one that allows the audience to go on “character journeys.” As the sannyasins speak, the sense of community and belonging they felt at Rajneeshpuram becomes clear, and I found myself empathizing at times with people I didn’t think I could care about.īut this narrative choice has downsides, too.

Accordingly, Wild Wild Country features in-depth interviews with former Antelope residents, federal prosecutors, and a handful of sannyasins. To their credit, the Way brothers have said they set out to make a documentary that would invite viewers to look critically at both sides of the story and decide for themselves what position to take. It’s a notable omission that highlights a problem facing many true-story works about cults and cult-like groups: offering a fair, sympathetic portrayal of the followers in the thrall of a charismatic leader, without denying them of individuality or responsibility. Still, for all its attempted comprehensiveness, Wild Wild Country fails to really consider the consequences of the Rajneeshees’ behavior for many of their families.

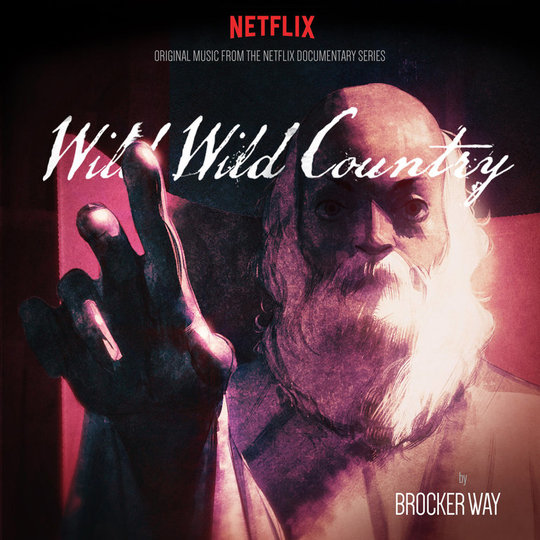

#Wild wild country osho series

This footage, along with lengthy interviews with former and current prominent sannyasins, is what lends the series its authority. That’s because the directors, the brothers Maclain and Chapman Way, had obtained countless hours of video shot from inside the group. Watching Wild Wild Country, I had to pace myself I was scanning every frame to see if I’d spot my mother. I Have Some Questions About the World of Teletubbies Sophie Gilbert But, as I learned, it’s much easier to devour a story that has nothing to do with you.

The tale may call to mind Waco, a docudrama miniseries about the standoff between federal agents and the Branch Davidians that I recently binge-watched. The series also features two larger-than-life characters who ultimately destroy Rajneeshpuram: Bhagwan himself, and his personal assistant Ma Anand Sheela, who’s depicted as the mastermind behind the group’s most shocking schemes, including an assassination attempt. Part of what makes Wild Wild Country so astonishing is that it chronicles a spiritual movement that inspired thousands of well-educated Westerners to leave their old lives in order to dance with abandon, have sex in what were referred to as “therapy groups,” and reach enlightenment.

Eventually, the group’s bizarre activities attracted attention from the federal government, leading to a spate of allegations for crimes including mass poisoning and immigration fraud. The Rajneeshees, as they were known, moved en masse in the early 1980s to the tiny town of Antelope, Oregon, where their efforts to create a utopian city called Rajneeshpuram upset local residents. At its heart, the six-episode series is about an upstart religious movement clashing with big government. Wild Wild Country proved lush and captivating, as it highlighted the magnetism of Bhagwan (later known as Osho) and the devotion of his thousands of followers (known as sannyasins). But a couple of weeks after the documentary’s release, I braced myself and sat down to watch. Though my mother made her way back into my life when I was in high school and we now have a close relationship, I never wanted to think about Bhagwan again. He stared at me from news sites with the same eyes I’d seen on book covers in my mother’s apartment-after she returned from his ashram in India, and before she left our family a second time to follow him to Oregon, where much of Wild Wild Country takes place. Even if I had wanted to skip the show, it’d have been impossible to avoid all the articles about the group’s leader, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. They wanted to hear what I thought about the documentary, which centers on the so-called cult my mother once belonged to. When Netflix’s hit series Wild Wild Country debuted in March, friends who know about my upbringing began messaging me.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)